This is a comparison of dbt (SQL) and Drizzle (TS) as an infra choice for Data Analysis. The findings seem to confirm my inkling that dbt might be more human coded than Coding Agent coded... I'm interested in hearing thoughts, as this is the first poke at this idea.

Way back I wrote a few blogs about the Modern Data Stack, this is the first look back into the space (and it was a brief look) since I stopped that and started a startup.

If you have any ideas for improving this investigation, I'm all ears!

----------------------------

Since reading the OpenAI data stack post, I've suspected that dbt/SQL might get in the way of LLMs when looking at the data stack more holistically.

By data stack, I'm talking Modern Data Stack: ETL core app data into Snowflake/BigQuery, load other API data like Stripe in as well, do SQL joins to get answers (if unfamiliar then this post might not be that clear).

All the SQL + metadata might just be more human useful than LLM useful.

Or the system might have been better designed for when we didn't have Coding Agents.

I've wondered about this a bit:

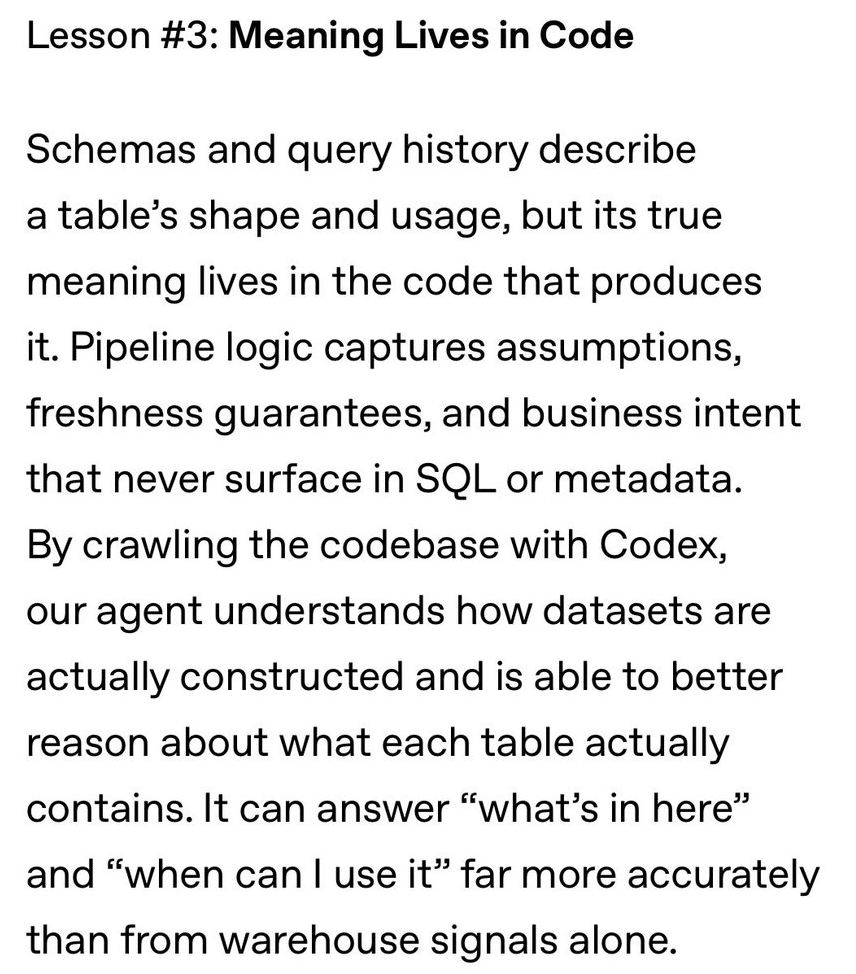

On a related note to dbt, a strongly coupled feeling, I've felt that your main app's code is underutilized as a source of meaning and structure:

Then I see this point from Open AI, and I'm like, YES!

I've felt this acutely. Maintaining SQL files in dbt has just so much surface area, and so little logic!

But also reading the OpenAI post, I see they are still running most of their analytics logic in SQL!?

I really struggled to believe that the OpenAI data, at the fastest-growing, most well-funded supercompany in recent memory, is doing exactly what I would do.

They are running the Covid era MDS at the core of all the other stuff.

Same way, same tools, driven by the same FinOps need.

I don't expect SQL to go anywhere, that is not what I'm getting at. I also don't think dbt should go anywhere necessarily. Standards are set in times of disruption, and if dbt is the analytics standard then so be it.

But I wanted to scratch the itch. So I built a benchmark.

I present The Modern Data Benchmark (or MDS Gym?).

A small experiment comparing how LLM agents perform across different data architectures, given the same data and the same questions.

The pro-forma result:

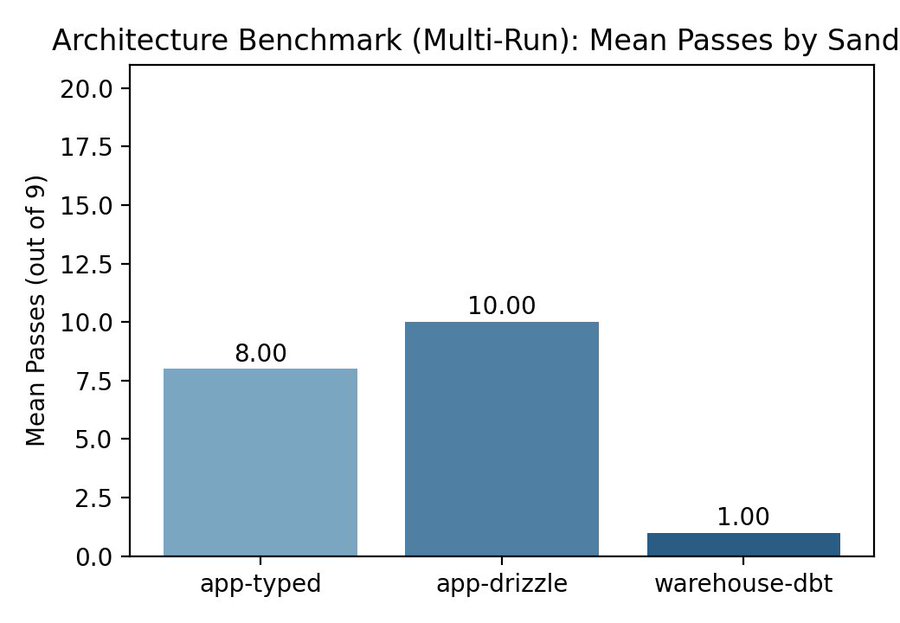

Across 7 LLM models, warehouse+dbt had a 5% pass rate. App-unified architectures had 38-48%.

*the numbers in this post are directionally correct, like the MDS.

A quick history of how we got here

Before we dive into it, some context.

The Modern Data Stack came out of a specific organizational need.

Marketing needs to track ad spend.

Finance needs to reconcile Stripe revenue.

These are important but non-core functions, so they get staffed by analyst-operator types who can usually write SQL but not Python. Add Redshift/Snowflake and all roads lead to you SQL.

dbt emerged to give those SQL queries just enough software engineering discipline, version control, modularity, templating, without forcing anyone to leave SQL. It was a rational solution to a real constraint: these teams could not write very good code, and didn't have a place to write it.

The gravity of that constraint pulled everything towards raw SQL against a data warehouse. No types, no abstractions, nothing but SQL. dbt came along to solve the obvious shortcomings (shitshow) of lots of SQL. Version Control+Jinja and it was, I was working in enterprise data before, dbt was wild!

OpenAI's data warehouse confirms the pattern

What surprised me was looking at OpenAI's data warehouse. On the surface it looked sophisticated: context layers, embeddings, all the works. But at the core, two things stood out.

First, it was driven by FinOps. The example given was revenue reconciliation from Stripe. Even at frontier AI companies, FinOps drives the data warehouse.

Second, it uses SQL (and I guess dbt). The team likely had used dbt before, so they reached for it again. This isn't a criticism, it's how standards form. Not by systematic evaluation, but by repetition.

The question worth asking

dbt's value was making SQL manageable for human analysts. But at scale there are now tens of thousands of lines of SQL that no human is ever going to read. The SQL is increasingly being consumed by agents.

If the consumer is an agent, "easiest for humans to read" stops being that important.

The relevant question becomes:

For an agent answering business questions, which representation of the system is the most legible, robust, and correct?

It all felt rather benchmarkable.

The split-brain problem

The modern data stack creates a structural split. Your app has your core business logic: users, statuses, transactions. Separately, you have a data warehouse that holds a lagging copy of that data, plus third-party data like Stripe that only exists in the warehouse.

To answer anything useful, you need to join app data onto Stripe data inside the warehouse, using SQL, with constrained logic. The "single source of truth" in the warehouse is never truly trustworthy. Your actual source of truth is the production database and someone else's API, and the warehouse is always behind.

The crux: what if you brought the data closer to home? Shift left? Strongly typed? Asked Codex 5.3 to spar with Opus 4.6 on turbo mode? What would they do?

I guess they'd load Stripe data into a structure your app understands, with proper types and constraints, and they'd run analytics against the unified codebase..?

If revenue is a key business capability, and we're no longer as code-constrained as we were, why not model it as a first-class concept?

(this has a million small holes, but stay with me)

The benchmark

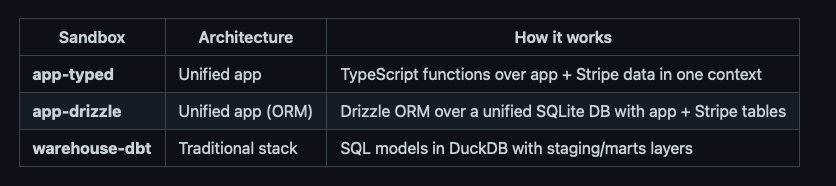

Three sandbox environments, same data, same three analytical tasks: ARPU, churn rate, and LTV.

Small data, known correct answers. Size isn't the test. We are looking at architecture.

In the app sandboxes, Stripe data is represented as internal data with types.

App Tables + Stripe Tables → Single typed context → Code → Metric

In the dbt sandbox, it follows the traditional pattern: third-party data loaded and joined via SQL.

App DB + Stripe → Replication → DuckDB raw tables → Staging SQL → Marts SQL → Metric

The model must discover the schema and produce executable code that returns the correct number. No hints, no hand-holding.

The key difference: in app architectures, the model has one typed context. In the warehouse, it must navigate staging models, column naming conventions, and SQL casting to arrive at the same answer.

How the evaluation works

Each run works like this:

Fresh sandbox. A clean copy of the sandbox template is created with the synthetic data loaded. No prior work carries over between tasks.

Agent loop. The model gets a system prompt describing the architecture and four tools: read_file, write_file, list_files, and done. It has up to 10 turns (API round-trips) to explore the codebase, discover the schema, write its solution, and signal completion. Temperature is set to 0.

No hints. The model is told what to compute (e.g., "ARPU for active users") and given the function signature, but not how. It must figure out join keys (users.stripe_customer_id → invoices.customer_id), column names, and time anchoring on its own by reading files.

Execution app-typed: the TypeScript function is imported and called with the data arrays.

Execution app-drizzle: the async function runs against a pre-loaded SQLite database via Drizzle ORM.

Execution warehouse-dbt: the SQL is executed in DuckDB with raw tables created from JSON (staging/mart views are built from any SQL files the model wrote)

Scoring. Pass/fail is purely numeric: does the output match the expected value within tolerance? (±1 for integers like ARPU/LTV, ±0.001 for rates like churn). No partial credit, no style points. If the code crashes, it's a fail. If it returns the wrong number, it's a fail.

Flexible matching. The validator accepts naming variations (calculateARPU, computeArpu, getArpu, etc.) and searches multiple directories for SQL files, so models aren't penalized for reasonable naming choices.

Expected values are computed from the same data by a reference implementation in the benchmark harness itself, not hand-coded, so they're guaranteed consistent.

THE RESULTS

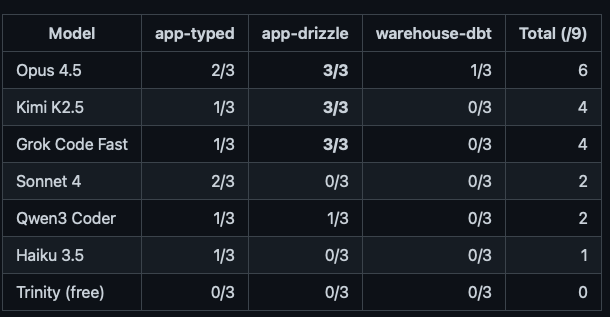

The ORM sandbox was the clear winner: Opus got a perfect 3/3 every single run, and cheaper models like Kimi and Grok matched it.

The warehouse-dbt column is almost entirely zeros. Only Opus managed a single pass, and even that was inconsistent across runs.

Looking closer at variance on multi-run stability (n=5 per Anthropic model)

Opus: Zero variance.

Sonnet: High variance (~0.9 std).

Haiku: Fluctuates between 0-1 passes.

Mid-tier models are at the edge, and the architecture is what pushes them over or pulls them back.

Where dbt struggles

The failure modes:

Schema mismatch: wrong column names (created_at vs usage_created_at, org_id vs organization_id). Staging conventions that the model has to guess.

Type mismatch: interval math on VARCHAR timestamps without casting.

File naming: incorrect output filenames or failure to write the metric model.

Even thorough models struggle with dbt

Adding in a measure of unique files read per task in warehouse-dbt:

Haiku: 1.1 files (barely looks at the schema)

Sonnet: 3.7 files (reads staging files but still gets column names wrong)

Opus: 4.4 files (reads everything, still only 1/3 pass rate)

Even when the model does its homework, the warehouse architecture introduces enough indirection to trip it up. It's not a laziness problem, the representation has too many seams.

In the app sandboxes, failures were simpler (wrong join key, missing function) and more recoverable in typed code.

What I take from this

This benchmark tests a narrow but important thing: can an agent read a schema, write executable logic, and return the correct metric? It doesn't test full dbt workflows with Jinja, ref/source, or materializations. It tests the core analytical task that everything else is built to support.

A few observations (not conclusions, this is early and the sample is small):

The architecture matters more than the model. The same model that fails at dbt can succeed in a typed environment.

ORMs are surprisingly agent-friendly. Drizzle over SQLite was the strongest sandbox, even mid-tier models could navigate it. Typed schema + query builder + unified context seems to hit a sweet spot.

Indirection has a cost that compounds. Each layer of staging, naming convention, and type casting is a place where an agent can silently go wrong. Types and co-location seem to reduce that surface area.

What's next

The current tasks (ARPU, churn, LTV) are intentionally simple, canonical SaaS metrics on synthetic data. The architecture signal is clear, but the questions need to get harder to be convincing.

A few directions:

What is a "fair" dbt project? After the initial results I started adding hints to the dbt sandbox to get some passing runs, things like cast annotations in staging models so the model doesn't trip on DuckDB timestamp arithmetic. I added

CAST(created_at AS TIMESTAMP) AS usage_created_atin the staging layer as it kept tripping up on that. It sort of helped: adding a single cast hint let Sonnet pass org_churn_rate where it previously crashed on a runtime error (details), but it wasn't that consistently helpful. It also felt like a slippery slope. How much documentation and scaffolding do you add before the dbt sandbox stops being representative of what an AI agent would setup. Remember this was all setup by Codex 5.2, I didn't touch a thing! A real dbt project lives somewhere on this spectrum, and where exactly is an open question. But maybe that's the point. You can keep adding scaffolding to SQL, cast hints, schema docs, Jinja templating, ref() pointers, semantic YAML, and each one closes a small piece of the gap. At some point you have to ask: is the SQL architecture, with all the scaffolding you need to make it work for agents, converging on the thing you'd build if you just started with types and a unified codebase?Realistic drift. The current benchmark is static, the data is clean and complete. Real analytics is messier: late-arriving Stripe invoices, missing stripe_customer_id mappings, schema changes mid-pipeline. Adding sync delay scenarios would test whether the split-brain problem is as bad in practice as it is in theory.

Linting as agent feedback. Early experiments with TypeScript typecheck + SQLFluff showed that giving agents lint feedback and extra fix attempts improved ORM more than dbt scores, but the improvement might just be from extra turns, not the lint signal. SQLFluff style rules seem to add noise that distracts smaller models. A schema-only mode that only surfaces missing tables/columns could be a cleaner signal. I tried some things there, but nothing clear.

Information parity. A typed codebase inherently carries more structural information (types, constraints, relationships) than raw SQL with YAML docs. You could argue that's confounding. I guess so? But that's also the point: the architecture is the information density. Still, enriching the dbt sandbox with comprehensive YAML schema docs would test how much of the gap is "types help" vs "unified context helps."

Turn-level analysis. Currently only tracking file-read counts. Understanding the step-by-step reasoning, where models go wrong, when they recover, would give sharper insight into why architecture matters.

Other interesting things:

Semantic layer sandbox (Drizzle-Cube). The baseline benchmark included Drizzle-Cube but the architecture benchmark didn't. Adding it would test whether pre-defined measures help or constrain agents. I'm hopeful this pushes Drizzle well beyond comparison!

Does the "context layer" exist? There's a lot of hand-waving right now about "context layers" and "context graphs." When you boil these down, they often look like a data warehouse or semantic layer in new language. My position: if you can't demonstrate a simple instance of a complex idea, it doesn't meaningfully exist. Next step is to build sandboxes for the best-case context graph blogs and run them through the same benchmark.

Harder queries. @matsonj's platinum set from the BIRD text-to-SQL benchmark covering complex joins, CTEs, NULL handling, and conditional aggregation. Also KramaBench which tests full data pipelines, not just single queries, and from the benchmarks referenced by Sphinx including DABStep (real Adyen payments data). If agents struggle with simple ARPU, what happens with real analytical complexity?

Costs. I tracked the costs, the results were somewhat interesting, it seemed like Opus was actually often cheaper as it took fewer laps to get the answer. I need to benchmark this more carefully. Pareto performance cost curve.

A request

I'm no longer that close to dbt. Things may have moved on. If you're actively working in dbt and you look at the warehouse sandbox and think "that's not how we'd set it up," I genuinely want to hear that. Is this a realistic task? Is this a fair test? The benchmark is open source, you can set up the dbt sandbox the way you think it should be, and run the same evaluation. If a well-configured dbt project closes the gap, that's a finding worth publishing too.

Caveats:

Small n, synthetic data, single-pass runs for some models, no full dbt compilation. This is directional, not definitive. Run it yourself, add harder tasks, prove me wrong.

Claude wrote this out from a voice-note I recorded.